|

Home > Ocean > Oceanography > Geography of the Sea > Submarine Canyons

Geography of the Sea: Submarine Canyons

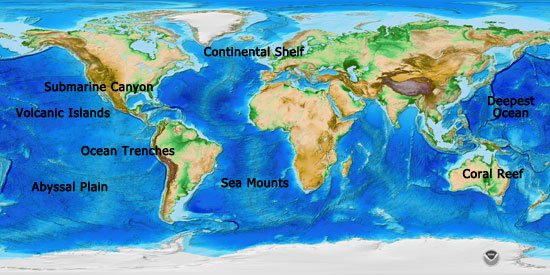

In many continental shelves submarine canyons have been found carving deep fissures that stretch from near shore out to the deep sea edge of the shelf. There are a number of theories as to what carved these giant cracks into the shelves, but the most prominent one states that sediment transport carved these canyons. Sediment transport in the sea occurs primarily as underwater landslides of enormous masses of rock and sediment, usually triggered by turbulent waters during a storm, or ground movement from an earthquake. The depth at which the submarine canyons have been cut depends on the make up of the underlying rock – how susceptible it is to being carved – and how much, how often and how heavy the materials are that are transported downslope during an underwater landslide. It is also believed that some canyons were carved above ground, at a time when sea level was a mile or more lower than it is today. Those canyons that are now submerged may have once held rivers and waterfalls that carved the canyon walls, carrying the sediment and debris down into shallower sea.

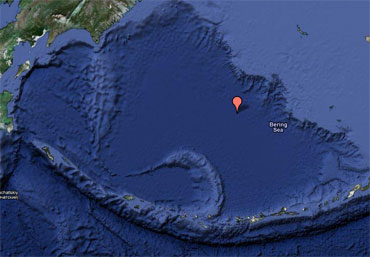

The largest and deepest submarine canyon ever discovered is in the middle of the Bering Sea called the Zhemchug Canyon. It is deeper than the Grand Canyon (1.83 km deep) at 2.6km deep. Zhemchug Canyon is the largest submarine canyon in the world, based on drainage area (11,350 km2) and volume (5800 km3). Deep, cold, oxygen-rich waters well up from the deeps into the canyon, providing sustenance to an enormous array and variety of life forms. The largest and deepest submarine canyon ever discovered is in the middle of the Bering Sea called the Zhemchug Canyon. It is deeper than the Grand Canyon (1.83 km deep) at 2.6km deep. Zhemchug Canyon is the largest submarine canyon in the world, based on drainage area (11,350 km2) and volume (5800 km3). Deep, cold, oxygen-rich waters well up from the deeps into the canyon, providing sustenance to an enormous array and variety of life forms.

|